The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick was already implied in Christ’s first mission to the twelve apostles. “So they set off to preach repentance; and they cast out many devils, and anointed many sick people with oil and cured them” (Mark 6:13).

Some time during His public ministry, Christ personally instituted anointing “as a true and proper sacrament of the New Testament” (Council of Trent, November 25, 1551). After the Lord’s ascension into heaven, anointing was commended to the faithful and promulgated by the Apostle James, “the brother of the Lord.” What St. James says is that the sick should be anointed. He also declares who is to perform the anointing and what effects are to be expected from the conferring of this sacrament.

If one of you is ill he should send for the elders of the Church, and they must anoint him with oil in the name of the Lord, and pray over him.

The prayer of faith will save the sick man and the Lord will raise him up again; and if he be in sin, they shall be forgiven him (James 5:14-15).

Among the few passages of Scripture that the Church has officially (and infallibly) defined are these two verses in the letter of James the Younger, or Less, who was a near relative of our Lord. According to the Council of Trent (November 25, 1551) the elders to whom St. James refers are “priests ordained by the bishop.

Sacramental Ritual

Until the Second Vatican Council, the anointing had to be with olive oil blessed by the bishop. This is still the ordinary material used in the administration of this sacrament. But Pope Paul VI decided that since olive oil is unobtainable or difficult to obtain in some parts of the world, in the future any oil “obtained from plants” could be used.

Moreover, in keeping with the directives of the Council, the ritual was simplified. The formal papal declaration deserves to be fully quoted.

The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick is administered to those who are dangerously ill, by anointing them on the forehead and hands with olive oil, or if opportune, with another vegetable oil properly blessed, and saying once only the following words: “Through this holy anointing and His most loving mercy, may the Lord assist you by the grace of the Holy Spirit, so that freed from your sins, He may save you and in His goodness raise you up” (Apostolic Constitution on the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, November 30, 1972).

In case of necessity, it is sufficient that a single anointing be given on the forehead. In fact, if the particular condition of the sick person warrants it, another suitable part of the body may be anointed, while pronouncing the whole formula.

The sacrament can be repeated under two circumstances:

- If the sick person, having been once anointed, recovers and then falls sick again.

- If in the course of the same sickness, the danger becomes more serious.

According to the directives of Canon Law, “the Anointing of the Sick can be administered to any member of the faithful who, having reached the age of reason, begins to be in danger due to sickness or old age” (Canon 1004).

As explained by Paul VI, “Extreme Unction, which may also and more fittingly be called ‘Anointing of the Sick’ is not a sacrament for those only who are at the point of death. Consequently, as soon as any one of the faithful begins to be in danger of death from sickness or old age, the appropriate time to receive this sacrament has certainly already arrived” (Apostolic Constitution). The key words are “begins to be in danger,” as contrasted with “at the point of death.”

The new code is also more lenient than the former regarding doubtful cases. “If there is any doubt,” the law now says, “as to whether the sick person has reached the use of reason, or is dangerously ill, or is dead, this sacrament is to be administered” (Canon 1005). This is a change from the former prescription that the sacrament “is to be administered conditionally.”

Two further provisions exist in the Church’s general law. One concerns the kind of desire a person must have to receive anointing, and the other concerns people who are living in notorious sin. On the one hand, therefore, “this sacrament is to be administered to the sick who, when they were in possession of their faculties, at least implicitly asked for it” (Canon 1006). On the other hand, “the Anointing of the Sick is not to be conferred upon those who obstinately persist in a manifestly grave sin” (Canon 1007). Between these two situations lies the whole issue of having the proper dispositions to receive the graces available through anointing.

Spiritual and Bodily Effects

The Church explains the words of St. James about the effect of anointing by distinguishing two kinds of blessing which this sacrament confers. The principal blessing is for the soul, the secondary is for the body.

How is the soul blessed by the Holy Spirit through anointing? In several ways:

- The guilt of mortal sin is removed, so that a sinner is restored to God’s friendship. With the guilt the eternal punishment due to mortal sin is also removed. On this level, anointing has the same effect as Baptism and the sacrament of Penance. Moreover, the sorrow required for remission of sin is the fear of God, based on faith, which makes anointing so precious. Even though a person is unconscious when anointed, yet he is restored to God’s grace with the minimum requirement of what we call imperfect contrition, which means sorrow for sin because a believer fears the just punishments of an offended God.

- Also, the guilt and temporal punishment of venial sins are removed, depending on the dispositions of the person anointed.

- Temporal punishment still due to forgiven sins is removed, again depending on the spiritual dispositions with which the sacrament of anointing is received.

- Anointing strengthens the sick person in especially two ways:

- Trust in God’s mercy is deepened by reassuring the one anointed that, no matter how deeply God had been offended, He is a loving God who wants only the salvation of the sinner.

- Courage is received to face the future, especially the prospect of death. A person is prepared to enter eternity with a peaceful acceptance of God’s will.

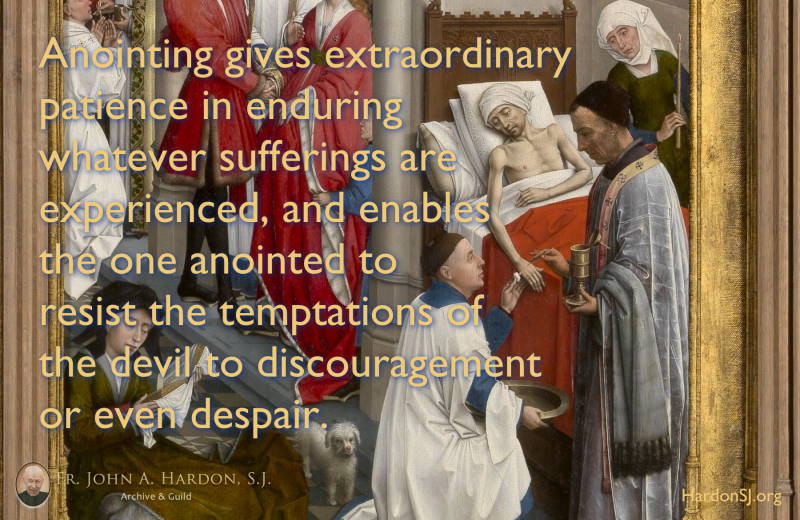

- Anointing gives extraordinary patience in enduring whatever sufferings are experienced, and enables the one anointed to resist the temptations of the devil to discouragement or even despair.

The Church’s teaching on the bodily effects of the sacrament is simply expressed. “This anointing,” says the Council of Trent, “occasionally restores health to the body if health would be an advantage to the salvation of the soul.” In other words, the spiritual effects of anointing are unconditional provided the sick person is properly disposed. But the benefits to the body, including restoration to health, depends on God’s foreknowledge of whether this would be good for the soul. Sickness is not an absolute evil. If God foresees that being healed in body is for our supernatural good, He will “raise us up” physically so that we might also be “raised up” spiritually and be more assured of our eternal destiny.

Pocket Catholic Catechism