by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.

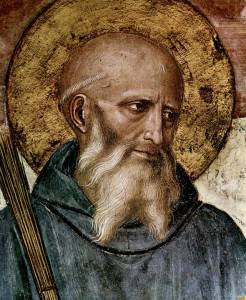

“We must know that God regards our purity of heart and tears of compunction, not our many words.” Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 20

Societies, like individuals, have distinct personalities. Or, more accurately, societies, no less than individuals, are as effective as they are distinctive, contributing their unique share to the welfare of mankind under the Providence of God.

Religious communities are no exception. They are so numerous in the Church, and so varied, because there are so many ways that Christ can be imitated – since God is infinite and Christ, who is divine, is infinitely imitable. They are also manifold because the Church wisely encourages different ways in which different groups can render varied service to the People of God, some by concentrating on prayerful contemplation and sacrifice, others by combining the roles of Mary and Martha through contemplation in action, and still others by moving rhythmically from prayer to action and back to prayer again.

They are further varied because the needs of the Church are so kaleidoscopic. In the Church are mothers who are giving birth to children, children of every age who need to be instructed; there are the sick and maimed, the weak and the handicapped; the confused who need counsel and the aged who wish to be cared for and loved.

And all the while we know that the corporal works of mercy are only the means for effecting spiritual change, even as Christ went about doing good to people’s bodies in order to reach and transform their souls.

Distinctive Identity

So much for the fact that there are different religious orders and congregations in the Church.

Our next question is how do these differences arise or, from another viewpoint, how are they identified?

These differences arise in societies, no less than in individuals, mainly from two sources:

- from differences of origin, and

- from each having a different history.

Suppose we look for a moment at each of ourselves. How come we are so different and therefore distinctive? Each of us had different parents, or if the same parents physically, parents who brought us into the world at different times, or even if by rare exception we were twins bodily, God infused different souls into these bodies at conception. In any case, our origins are unique. Each of us began as a distinct individual.

Again, each of us, since conception and birth, has had his or her own history, which we call our autobiography. Our experiences within and our experiences outside of us have been our own and one else’s.

As a consequence of both factors, of our unique origin and our own personal history, we are we. We are in a word, distinct persons with distinct names that stand for distinct individuals. We have our own identity.

If we apply these two norms to the moral persons, which are societies, and, for our Purpose, religious communities, we see the same principles operative.

Benedictines are not Franciscans, Dominicans are not Jesuits, Carthusians are not the Camaldolese, Ursulines are not the Sisters of Notre Dame, and so of all the religious families in the Church for two main reasons:

- because each religious family, and within the family each community, had its own founder or foundress who infused into it his or her distinctive spirit,

- and because this spirit, animating just this body of religious men or women, has had its own communitarian biography.

We could, at this point, begin to compare the relative importance of origins and history in distinguishing one religious community from another. But the comparison, though interesting, would not be very useful. Why not? Because in the life of societies, as of individuals, the two elements are really inseparable.

Our origins will forever shape our history. And our history is the outgrowth and development (or regression) of our origins.

Spirit of the Founders

Yet between these two factors, there is no doubt which one is primary, not only in time because it came first but in essence because without it nothing else could follow.

It is the distinctive spirituality of the founders. Taking stock of this priority; the Second Vatican Council declared:

It is for the good of the Church that institutes have their own proper characters and functions. Therefore the spirit and aims of each founder should be faithfully accepted and trained, as indeed should each institute’s sound traditions, for all of these constitute the patrimony of the institute. (Perfectae caritatis, 2)

Thus, according to the mind of the Church the following principles of renewal. (as the basis for adaptation to the times) are required:

- Each religious institute should be distinctive. This is good for the Church, so that obscuring or blurring such distinctiveness is bad for the Church.

- This distinctiveness consists in having a unique character (or personality) and what follows as a result a special work in the apostolate. A characterless community is like a characterless individual. They are both ineffective. So, too, each community should concentrate on some particular apostolate, even though it may give attention to a variety of human needs. A scattered apostolic zeal going in all directions at once dissipates the energies of societies no less than it drains, with lowered achievement, the resources of persons.

- Such community distinctiveness, the Church tells us, must first be acknowledged. A synonym for acknowledged is recognized, which means it must be identified. It is not something so vague and amorphous as to be unintelligible. Otherwise what good is it? And, once identified, it should at all costs be preserved.

- Concretely the identity is recognized first in the spirit and intentions of the founders. Note that we have here two qualities of the founders which set the pattern for a religious institute.

- the spirit of the founder, which is his or her special charism or supernatural gift by which God animates this institute, and

- the aims or intentions of the founder, which are the purposes or goals he or she sought to be accomplished in and by this particular community; in the community through the special ways in which Cod would be honored and Christ the God-man would be imitated; and by the community through the special apostolic labors that its members would perform for the extension of God’s Kingdom.

- Also concretely the institute’s identity is recognized in the sound traditions – let us stress sound traditions – which form its authentic heritage. These traditions are the founder’s spirit lived out by those who inherited it.

- Finally, and most pertinently, it does no good to merely recognize this identity. It must also, the Church reminds us, be preserved. Preservation of the community’s identity is the indispensable precondition for valid renewal. Without it there is revolution but not renovation.

The Church wants religious institutes to know who they are, so that – knowing who they are, they can then be themselves.

Only on these conditions is it reasonable or even possible, to talk about adaptation to the times or of adjustment to changing circumstances of the age. Unless deep interior renewal, according to the spirit of the founder, precedes adjustment to the times, the times will so completely change an institute that it will even cease to be a religious community. Adaptation becomes senseless conformity whenever societies, no less than individuals, forget their distinctive personalities, when they barter their rights to be themselves for the sake of temporary expedience or the fear of a passing criticism of not being relevant to the times.

Into the Future

One statement of the conciliar decree on the up-to-date renewal of religious life has been surprisingly overlooked in much of the current writing on the subject. It touches directly on our theme of “the one and the many” in religious communities.

Institutes and monasteries which the Holy See, having consulted the local ordinaries concerned, judges not to offer any reasonable hope of further development, are to be forbidden to receive any more novices. If possible, they are to be amalgamated with more flourishing institutes or monasteries whose aims and spirit differ little from their own. (Perfectae caritatis,21)

Amalgamation with more flourishing institutes or monasteries are to be done, as far as possible, with communities that have more or less the same spirit. There is great wisdom in this recommendation. It presumes that where communities have either the same origin or the same original purpose in serving the Church, this kind of amalgamation is thoroughly feasible. So far from having to be mandated from above, it should be sought spontaneously (and realistically) by the handicapped communities themselves. Over the centuries it has often been accomplished with great benefit to everyone concerned.

But this also presumes that the amalgamation is done in favor of “more flourishing institutes or monasteries.” By now it is becoming more and ‘more clear which are the more flourishing communities. They are those that attract postulants and novices to their ranks because they offer a sound prospect of a lifetime commitment of sacrifice in the following of Christ and service of His Church.

Another recommendation of the Second Vatican Council deserves more attention than it has been getting. Having declared that amalgamations may be necessary to save some faltering communities, the council went on to favor the creation of federations, unions or associations with a view to strengthening their separate institutes.

Institutes and monasteries should, as opportunity offers and with the approval of the Holy See, form federations, if they belong in some measure, to the same religious family. Failing this, they should form unions, if they have almost identical constitutions and customs, have the same spirit, and especially if they are few in number. Or they should form associations if they have the same or similar active apostolates. (Perfectae caritatis, 22)

To be carefully noted is that three different terms are used to describe three very different kinds of cooperative enterprise, in varying degrees of coalition.

Common to all these ventures is that they be done with the approval of the Holy See. They also presume that, although juridically distinct, many communities either “belong to the same religious family,” or “have almost identical constitutions and customs, or “have the same spirit,” or at least “have the same or similar active apostolates.” The implication is that today, perhaps more than ever before, there is need for collaboration. Individual communities, faced with the challenges of a communitarian age, are hard pressed to retain their identity and even their character as religious unless-paradoxically they cooperate with like-minded communities to strengthen their own commitments as religious institutes in the Roman Catholic Church.

Where there is question of creating a formal union, the Church requires that there be kept in view “the particular character of each institute and the freedom of choice left to each individual religious”(Ecclesiae sanctae, II, 40). Of more than passing importance, too, is the provision that “the good of the Church must be kept in view” (ibidem). This means many things, but it certainly includes the proviso that the basis of any union or federation be the teachings of the Church and not just the personal ideas of some individuals. After all what matters in things of the spirit is not the obvious strength that comes from created numbers but the invisible power of truth that comes from the uncreated God.

On the level of forming associations among communities that “have the same or similar active apostolates,” this is a desideratum that not only the Church’s wisdom but the complexity of the modern age recommends. But again a proviso. This presumes that the grounds of association are those of the Church’s hierarchy, under the See of Peter, which is “guided by the Holy Spirit” to guide religious in their distinctive pursuit of holiness among the People of God.