History of Religious Life

St. Augustine and the Religious Life

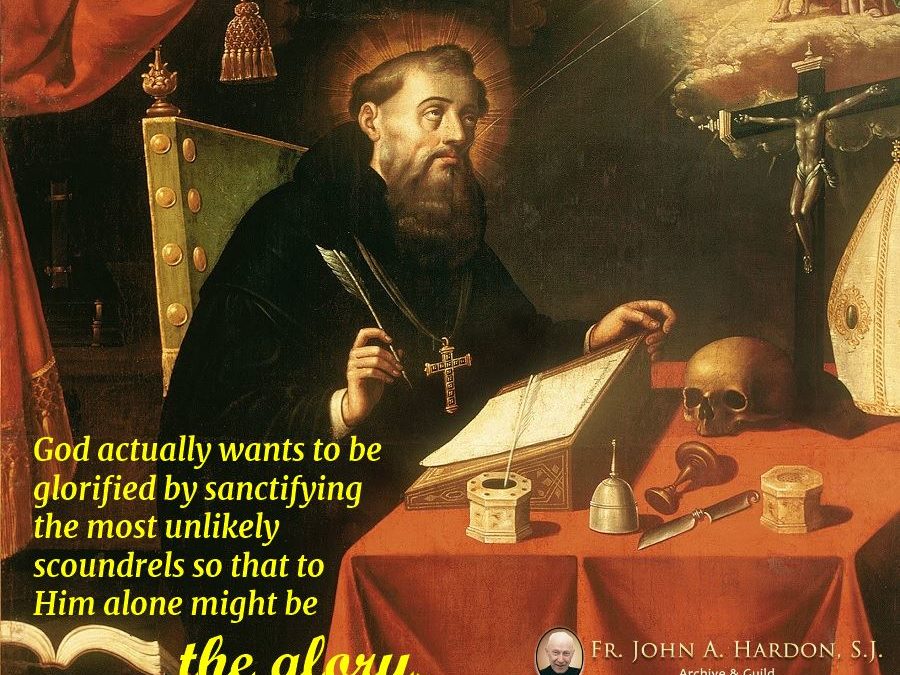

by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.

The Institute of Religious Life and the Daughters of St. Mary of Providence bring you the fourth in a series of lectures given by Fr. John A. Hardon S.J. on the theme: History of Religious Life. Father Hardon is a Professor of Theology at St. John’s University in New York. He is a well-known lecturer and consultant to various national, religious, and educational enterprises and is renowned as a retreat master and spiritual director. Fr. Hardon is the author of many articles and books, including Holiness in the Church and the Catholic Catechism, which has been strongly endorsed by Holy Mother Church. In the following Chicago lecture Fr. Hardon speaks on the subject: St. Augustine and the Religious Life. Father Hardon.

Augustine – Greatest Single Genius in the History of the Church

The subject of our lecture, therefore, is the contributions of St. Augustine to the doctrinal principles and community structure of religious life. The best way to approach St. Augustine’s doctrinal teaching is to see what were the principal heresies that he had to combat during his day. An understanding of those errors is to understand Augustine because and he was the one who in fact expressed this truth: God permits evil in order that greater good will somehow come out of the evil which He allows; and He permits error that a deeper understanding of the truth might be one of the fruits of the error that God permits. Augustine, by all odds, is the greatest single genius in the History of the Catholic Church. St. Paul, of course, as an apostle towers above everybody else except Christ Himself but then, Paul is in a class by himself. Among the post-apostolic giants of Christian religion none compare with Augustine.

Augustine’s Writings Are Numerous and Extensive

All of us, in greater or less measure, are familiar with the life of Augustine. It comes in several stages. He was born of a Christian mother and a pagan father, until the age of thirty-three he lived, as he admits, a very sordid even godless life. He had been for nine of those thirty years a Manichean. The two main reasons for his conversion as he himself testifies: the first, the prayer and tears of his mother Monica, and the patience and wisdom of Ambrose. His mother saw him converted and died as we know shortly before he became the, or, began to become the great man we know. Augustine’s writings are numerous and extensive. I suppose the best known of his works is his Confessions. There are many standard editions. This is one of the most readable translations by Frank Sheed, Confessions of Augustine written in American English by a man who understands the Latin and who appreciates the depths of Augustine’s thought. The Mentor Omega paperback – mentor omega edition of the Confessions is also a good one. Everyone should have read certain books in their lifetime – this is one of them. My recollections of reading the Confessions of Augustine were during – I think it was Latin class in high school – when the Marianist Brother came to see what I was doing so intently in the back of the room. He said, “I’m pleased with your reading but this is not the place or the time.” Well, I then proceeded to show my attention in listening to, I think it was Latin. His most important work is the City of God – that too should be read. It is much harder reading especially the first perhaps third of it, but his wisdom is pretty well synthesized in those two works. There are several hundred of his letters; there are some two-score volumes and there are by now many pseudo-augustinian works; writings that are purportedly by Augustine. Maybe parts of them are by him but others by someone else. In any case, Augustine, I suppose, is the most plagiarized man in history.

Three Principal Errors and Doctrinal Principles

What were the principal errors that he fought and as the consequence of which gave us the doctrine that ever since has become the foundation of even Christianity, not to say, religious life? The three principal errors were Donatism, d-o-n-a-t-i-s-m, Manichaeism and Pelagianism. Many of Augustine’s writings are called anti-Donatist, anti-Manichean, anti-Pelagian which will not appear in the title in the scholarly – those are the three main divisions of Augustine’s writings. Now his sermons were different because they were given to the faithful in the light, of course, of the errors he was combating but there are many commentaries on the Scripture that Augustine have left us. There is a difference, however, between the commentaries on Scripture which, by and large, were heard by his audience and then taken down, more or less I might say faithful to his thoughts; and his letters that he himself wrote or dictated and also his treatises that he wrote. So the sharpest and clearest thought is found in his written treatises.

What do we find in each of these three errors that he thought especially as relative to religious life?

First Heresy – Donatism

The schism and later on the heresy of Donatism arose as a result of the persecutions in the early Church. We rightly glory and are proud of the numerous martyrs that the Church had for the first three hundred years – all the Popes were martyrs and no doubt one reason why we had no non-Italian popes for the last 450 years is because the last non-Italian pope was assassinated – not common knowledge. In any case, martyrdom is the glory of the Church; but along with the martyrs there also were many apostates.

Very Human But Tragic Problem

The problem that gave rise to the error of Donatism was a very human but tragic problem. As the persecutions waged some Christians, in fact many of them, gave up their Faith which could be done in a variety of ways. For example, one way was to turn over the sacred writings that the Christians would have; another way would to be to step on the Cross or pronounce a blasphemous phrase towards Christ; or sacrifice infants to one of the idols. In any case, out of fear of death or imprisonment many apostatized. Among those who apostatized was a North African bishop.

Those Who Had Given Up the Faith Wanted to Come Back

These persecutions came and went. One result was that, often, after the persecution would let up those who had given up their Faith wanted to come back. So what happened in this case? The bishop would apostatize, well, repented and wanted to go back to practicing his Episcopal Office so some of the Bishops said, “Sorry once you apostatize you lost everything. You lost your Christian character. You lost all the effect of the sacrament of Confirmation. You lost your priestly character. You may practice a long period of penance and then maybe be re-baptized, re-confirmed and re-ordained.” And that in a nutshell is the heresy of Donatism. The name comes from a Bishop Donatus who became the object of this kind of controversy in North Africa.

Helped with the Church’s Understanding of Who Belongs to the Church

Augustine fought against this idea and in the process he helped develop the Church’s understanding of who belongs to the Church, because what the Donatists were, in effect, saying is that the Church that Christ founded is a church exclusively of saints: that when you sin, say, by apostasy or other grave crimes – well, sorry, you used to be a Christian, but no more. If you enter the Church by baptism, you leave it by grave sin. And then depending on the part of the Church, in some places there is almost no re-instatement even possible; in other cases, repentance perhaps, at the moment of death. Clearly, that’s not the Church that we know today. Some are now scandalized at the Church’s patience with sinners in going, if you wish, to the other extreme. Look at all the sinners we’ve got; why don’t we clean up the Church? Well, a good idea, but the Church has learned a lot over the centuries – and one thing that She now knows, thanks in large measure to Augustine’s genius that as Christ foretold there would be in this Church – remember the parable of both good fish and bad fish – as one who is not a fisherman I wouldn’t know the difference. In any case, the figure of speech is valid. As we also know at the end of the world, there will be the sheep and the goats. Throughout the Gospel, Christ couldn’t have made it plainer that His Church is, indeed, the church of potential saints but of a lot of actual sinners.

Who’s Calling Whom A Sinner?

It is interesting to note that when the chips were down and Augustine had to defend the Churches being a Church not only of the holy but also of the unholy, that often that those who stood in judgment of their fellow Christians were not so holy themselves. This, in fact, was one of the arguments that Augustine used: “Who’s calling whom a sinner?”

Several Levels of significance

What is the significance of the Church’s teaching in the controversy of Donatism led by Augustine for us religious? Several levels of significance.

Efficacy of the Whole Sacramental System Was At Stake

First, because of that controversy, the Church now teaches with unmistakable clarity that the admission of the sacraments – pardon me – admission to the sacrament or administration of the sacrament does not depend on the holiness of the one who administers. It was Augustine that coined that beautiful phrase, “When John baptizes, it is Christ who baptizes. When Peter baptizes, it is Christ who baptizes. When Judas baptizes, it is Christ who baptizes.” The sacraments we receive, the Masses we attend, provided the one administering the sacrament or offering Mass has the power and the minimal intention to do what Christ wants; we get all the benefits. That is not unimportant, because the efficacy of the whole sacramental system was at stake.

Christ Came to Call Sinners to Repentance

Secondly, as Augustine made so much effort to make plain – inasmuch as we believe on Christ’s own testament that He came to call sinners to repentance. The very hope for sanctity presumes that the one who wants to become a saint, is a sinner! And what is most comforting, and I don’t think I’ll be always as clear as I should be in a few minutes I will spend on this subject; but is this ever practically important for most people as Augustine says “progress in holiness is progress against our sinful drives and passions.”

Church of Sinners Striving to Become Saints

How do you become a saint? Oh, that’s easy! Cope with your sins. And you can almost predict the kind of a saint that God wants you to be. That’s easy. Take the list of seven capital sins. Which one is predominant? That’s usually it. And in case we don’t know, ask somebody you live with, they’ll tell you. Congenital laziness, personification of indolence, nice, sweet but lazy; or a trigger temper – whenever you want, you never tell her to do anything; you always ask, and then to protect yourself, you use a mediator. The sins that we are most prone to are the index of the virtues that God wants us to specialize in. So that the Church is a Church of sinners who are striving to become saints. I cannot tell you how consoling that is! Because you say to yourself, well, gosh I really belong to the Church! I really do, because I qualify.

Efficacy of Grace Depends Mainly on Christ

A third profound insight that Augustine brought out, in his volumes of controversy with Donatism, is the efficacy of grace depends mainly on Christ. That if it was left up to us, none of us could even aspire to be saved, let alone, to be a saint. And that God actually wants to be glorified by sanctifying the most unlikely scoundrels so that to Him alone might be the glory. And here Augustine knew – he had no allusions about Augustine’s strength of character – none whatever: Reliance on Christ.

Second Major Heresy – Manichaeism

The second major heresy that Augustine fought against so many volumes, was Manichaeism. Manichaeism, as I’m sure you have heard more than once, originated with an Oriental who became a Christian by the name of, well, Manichios. After becoming a Christian he decided that what he had been taught was less than true. It is not clear just how much Manichios himself held and how much of what is now called Manichaeism was the result of the speculations of his followers. In any case, by Augustine’s time it was plain enough; according to the Manichaeans, the only explanation of evil in the universe is to postulate two gods; a good God who is the originator and the provider of which, if you wish, with everything good; and an evil god who is the perpetrator of everything bad.

As the Manichaeans held, how could you postulate one god and yet admit there is evil in the world? Either that evil – this is a famous Manichaean dilemma – either that evil is illusory or it’s real; and all the evidence indicates it is not illusion. It’s real; moral evil, physical evil, sin, treachery, crime and suffering. If this evil is real, they defied the Christians to show how one good God could be responsible for this evil. And speaking in 1978 let no one tell you that you can shrug that objection off by a smile. In fact, as I’ve told my students for over twenty years; “There is no more incisive objection that the human mind can conceive, because it touches on the deepest mystery on earth – the mystery of evil.”

Champion of Human Freedom

Augustine having been a Manichaean for nine years understood the system well. It took a long time for him to see the errors of either Manichaeism or of his own, in particular. What he discovered is very valuable for us religious or, with God’s will, religious-to-be because as Augustine said, “If you look at the Manichaean explanation of evil, especially moral evil, sin – frankly, what does it say?” It says, in so many words, that all the evil is due to a god, an evil deity outside of you. “How convenient,” this is Augustine, “how useful,” because then no matter what you do, it’s not really you doing it. When it dawned on Augustine and by that time he was wallowing deep in his lechery as he says, “once it dawned on me that the same Augustine who is sinning had the will power (with God’s grace) not to sin; that was a new discovery.” Augustine is a great champion of human freedom, of man’s ability to make what he wants of his life. Many followers of Augustine – one that I remember – Francis de Sales – why he asked – this is de Sales – a great admirer of Augustine: “Why are there so few saints, comparatively speaking? Very simple, very simple! It’s not because more people don’t get the grace. It’s because more people don’t use their will power.”

Most Common Heresy in the World Today

In other words, the Manichaean heresy is an expression of what we call in philosophy – determinism, that we are determined or, if you wish, pre-determined according to you name it what; the modern form of determinism is – heredity, environment and education. So billions are being spent because of this illusory hypothesis; that virtue is in the suburbs, and vice is in the slums that provided people are born, well, of virtuous parents, they will be virtuous too. Not true, eh? Provided people are properly educated in knowing what is right and what is true – they will infallibly turn out good. Not so. Provided people live among good people, holy people, nice people, virtuous people; they’ll be nice and good and holy too. All heredity, education and environment strongly favoring practice, of course. It is just latter day Manichaeism. Millions of Americans that couldn’t spell the word Manichaeism or Manichaean; I believe that this is the most common heresy in the western world today: Few people have the will power, even make a decision. I don’t say a life-long decision, just a decision! Or to make up their own minds, they’re constantly feeding their minds – from the outside. Consequently the Church’s teaching on free will and its power is in large measure due to the impetus that Augustine gave it in its conflict with Manichaeism.

Pelagius Denied the Need of Any Grace from God

Third, the heresy of Pelagianism, P-e-l-a-g-i-a-n-i-s-m: Pelagianism is the one major heresy that Great Britain, specifically, the English can take for credit. Pelagius was a British monk. He made the mistake of leaving England and traveling – as I’ve told so many people unless you have the grace, don’t travel. You’ll be exposed to many whims. Pelagius was. He saw some very misbehaving people, especially bishops, priests and religious. He was scandalized and if you can imagine one heresy being the opposite of another; Pelagianism is the opposite of Manichaeism. Pelagius said, “I don’t have that trouble with that misbehaving bishop or that bad monk or nun is – I know the problem. They’re not using their will power. That’s it. And in time, he went around thinking, preaching, gaining a following. In time he came to deny the need of any grace from God. All you need is a strong backbone, will power – who are the saints, the titans of will power – who are the sinners, those who have a weak will.

No Supernatural Good without Divine Grace

When Augustine heard about Pelagius, he couldn’t believe it. It can’t be! Augustine, by that time, knew what kind of will power he had. He thought, at first, the man must be joking; he can’t be serious. When he found out so many were following Pelagius that he decided to enter the list against him. When it finally dawned on Augustine that Pelagius was a real heresiarch that’s an arch heretic, a heretic who makes other heretics – that’s Pelagius. You know the qualities of a good, effective heretic – that’s Pelagius. He was smart. He spoke and wrote well. He was ascetical. Contemporaries say he was skin and bones. He ate very little. He fasted a lot. He was the picture, if you please, of sanctity. So he misled in time, millions. The heresy lasted, we don’t know how many years, and it raged four centuries and it has infected the Church and its parts of Christianity ever since. Augustine here was at his best because here he could be very autobiographical. He seldom resorted to sarcasm, but with Pelagius he did. Augustine explained, as he knew from experience, without God’s grace we can do nothing in the supernatural order, not even a single supernatural act can be performed without divine grace as Christ made plain in one of the most important texts in Revelation that we have to memorize in our sleep, in theology 15:5 of John. Guess what it says? Without me, you can do nothing! No supernatural good without divine grace.

Grace Is the Remedy for Our Fallen, Sinful Nature

It was Pelagianism that forced the Church through the genius of Augustine to clarify its position of the two lives that we live: the natural life and the supernatural life. The life of nature of which we are born and the life of grace that we must be given. Out of the conflict therefore with Pelagianism, Augustine covered the gamut of the Church’s Theology of Grace. Grace is divine life; grace is invitation. Grace is the remedy – oh, how Augustine emphasized that – the remedy for our fallen, sinful nature.

Some of Augustine’s statements in his anti-Pelagian writings are so outspoken in describing man’s inability to do any good that centuries later he was picked up by John Calvin; and then Augustine – if he could suffer in heaven – what anguish it would have caused him to see himself used by Calvin as the foundation for predestination: that man’s nature is totally depraved. Well, Augustine never really, never really meant that although as he himself admitted (and this is to his credit) before he died Augustine published a whole book of Retractations – things that I said that I shouldn’t have said. Before I die I want to make sure that everybody knows what I really meant. Many of the passages of the Retractations are former passages of Augustine in which he says what a massa domnata – human nature is, that’s one of Augustine’s famous phrases. There’s no other translation in English for this except – damned. And then you can translate this in different ways; I sometimes translate it – mess. “Human nature is” – I’m quoting Augustine – “a damned mess.” Augustine, therefore, from years of sinful living had no weird idea, no illusion of what human nature is apart from Christ – that’s what it is. What he didn’t mean and he made sure before he died that nobody misconstrued him. He did not mean that we’re so utterly depraved that we cannot, for example, exercise any more will power. He didn’t mean that. He did mean, however, that we can do no supernatural good without grace. And we can, surely, acquire no virtue without grace.

Prayer: Key to Retaining And Growing in Grace

Augustine as a consequence is the great – and there are different names he is given; He is the doctor gratiae – the teacher of grace. No one has spoken more eloquently about the absolute indispensability of grace to do any supernatural good and of course to aspire at sanctity. He is also the doctor orationes – the teacher of prayer. The passages of Augustine on the necessity of prayer are among the most beautiful in Christian literature. And I thank him this morning’s class, if he was here that no salvation without grace, no grace beyond what God gave us and even that we lose without prayer. Prayer is the key to retaining and growing in that without which no one sees the face of God. So much for his doctrine.

On Community Structure of Religious Life

Let me just say a few words and take our break and go on to Benedict. First, I trust you had a chance to read the Rule of St. Augustine. It is the standard Rule that is now followed by every Augustinian and certain religious orders and congregations that are based on the Augustinian principle. There are really two Rules of St. Augustine. There was one for men and one for women although, by now, each Rule has influenced the other and what goes as the Rule of St. Augustine is not necessarily that which originally left his hand; unlike the Rule of Benedict, which is Benedict, period. The one for men was drafted for his own clergy. Augustine, even before he became a bishop, but later on as Bishop of Hippo decided to organize his priests or his priest-to-be in a religious community, as we would now call it. I suppose the men of the diocese had the option of going to another diocese if they didn’t want to become religious or monks.

Augustine Clericalized Religious Life

In any case, that is the masculine Rule. What Augustine has done therefore, or did for religious life is to make religious of clerics. Augustine clericalized religious life, That doesn’t mean that, even to this day, most religious are priests. And that, by the way, would be true even among men religious which may surprise you. Most Trappists in the world are not priests; just to mention one, one type of monastic living. However, the idea of priests being religious and living a religious life as priests was Augustine.

Asceticism of the Will: Obedience to Rule

For women he drew up a very detailed Rule which again I have the option of getting you copies of that to read and what I may do, except that I don’t want to just load you with a lot of paper, because I do want you to read whatever you’re given. Read that. But there is also a Rule that he drew up for women in his own diocese that has become a standard for women religious in the Catholic Church. Now there, too, the group was essentially contemplatives as were men’s groups – pardon – as were some men’s groups and all women’s groups in the early Church. As far as structure goes, Augustine recognized on the one hand as we’d just been saying, the importance of not denying the necessity of free will and, therefore, freedom that a person exercises in becoming a religious in the first place and knew he wants freedom but not so much in ascetical practices. Augustine was not so strong in asceticism commonly understood. He was very strong if you want to use the word asceticism – in urging asceticism of the will: Obedience to Rule. And in fact the Rule itself just to have a Rule of life for Augustine is already to be a religious. And there is norm called a regula, which is simply the Latin word for rule from which our English verb is derived – regulate or regular (writing on the board) regulate.

Sacrifice of One’s Own Preferences and Desires

So the asceticism of really conforming myself to a pre-conceived plan approved by the Church – in his case by the Bishop, which he was – serves all kinds of purposes: Serves the purpose of requiring sacrifice of one’s own desires to conform to the Rule.

The last thing you might want to do at a particular time is to go to eat. But the bell rings, but you’re not hungry. That’s not the point. But I’m not hungry! So what? You go to eat. Or the last thing that you might be in the mood to do is pray – You want to do something else. So, sacrifice of one’s own preferences and desires.

Secondly, Charity is fostered by regular living. Notice how we’ve changed the meaning of regular. It has the idea of periodicity, right? That’s not the real meaning of regular. The real meaning of regular is “according to rule.” According to a pre-conceived and pre-determined norm, because then each has to defer somehow to the other. And above all a Rule fosters unity. The two Rules of Augustine – one for men, one for women; both have affected all religious life since, with however one observation: There was a mildness, a lack of severity in Augustine’s understanding of religious life that stood in stark contrast, with say the Rule of Pachomius also in Africa, remember Hippo was in Africa. Augustine realized that the most important sacrifice that a human being can make to God is not of the body (but that too should be sacrificed) but of the spirit of both mind and will. In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Conference transcription from a talk that Father Hardon gave to the Institute on Religious Life

Institute on Religious Life, Inc.

P.O. Box 410007

Chicago, Illinois 60641

www.religiouslife.com

Copyright © 1998 by Inter Mirifica