Devotion of St. Thérèse of Lisieux to the Blessed Virgin Mary

by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.

A new stage is developing in the devotion of the faithful to St. Thérèse of Lisieux. In 1947, the fiftieth anniversary of her death, a congress of theologians was held in Paris with the object of studying the theological implications of St. Thérèse’s spiritual doctrine and of tracing her relationship to the other ascetical writers of the Church. Among the phases of Thérèse’s spirituality, her devotion to the Mother of God deserves special attention. For if, according to sound theology, all graces are given to us through Mary, the extraordinary graces which made Thérèse, in the words of Pius XI, “a miracle of virtue” should be no exception, as even a summary analysis of her life will fully confirm.

The Little Flower of the Blessed Virgin Mary

“The greatest saint of modern times,” as Pius X described her, was also one of the most devoted lovers of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This is the opinion of the Italian Mariologist, Gabriele Roschini, writing in his collection of Marian sketches, Con Maria, Editrice Ancora, Milan. The present analysis is based largely on this study.

Shortly after her religious profession, as the consecrated spouse of Christ, Thérèse painted a symbolic picture of herself. It showed a snow-white lily, symbolizing her soul, above which was a glistening star tracing the letter “M” – Marie – and letting fall its rays into the open petals below. She used to call herself, “the Little Flower of the Blessed Virgin,” and Mary, on her part, was called her “heavenly Gardener.” When she received from superiors the order to write her life, she immediately had recourse to Mary. “Before I took pen in hand,” she writes, “I knelt down before the statue of the Blessed Virgin, which had given to my family so many proofs of her maternal protection, and I begged her to guide my hand and not allow me to write a single line that might displease her.” (Autobiography, 15)

The Queen of the Martin Household

Thérèse Martin came from a household where the Mother of God may truly be said to have ruled as Queen. A statue of the Immaculate Conception – made of plastic and measuring 36 inches in height, which had been given to her father as a young man – occupied the place of honor in the house. Before this statue Thérèse’s mother consecrated her nine little children, one after the other, shortly after birth, and gave all of them as their first name, the chosen name of Mary. Gathering around the statue every night, M. Martin led his family in common prayers. And after prayers, each child was allowed to render some special homage to Mary’s statue, which, we are told, would often have to have its fingers replaced after the children had scrambled all at once to kiss Our Lady’s hands.

The Martins belonged to the parish of Our Lady of Alencon. As one child after another was given to them by God, the father and mother joined in asking the Mother of God that all their children might be consecrated to the service of her Son. Their prayer was not unanswered: four of the children died in their baptismal innocence, shortly after birth, and the other five, Pauline, Marie, Léonie, Céline and Thérèse, were consecrated to God in two orders of the Blessed Virgin, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel and the Visitation.

The Blessed Virgin in Thérèse’s Early Life

Thérèse was born January 2, 1873, at Alencon. The following day, in the Church of Our Lady, she was reborn in the life of divine grace, with the name Marie-Francoise-Thérèse. Less than five years later, her mother died at the early age of forty-six, and Thérèse’s character underwent a complete change. From “having been so vivacious and expansive,” she became “timid, meek, and sensitive to an extreme.” The void left in her heart by the loss of her earthly mother drew her instinctively towards her heavenly mother Mary. When she made her first confession at the age of five, her confessor exhorted her to a filial love of Mary. “I remember,” she says, “the exhortation with which he then urged me above all to a devotion to the Blessed Virgin; and I promised to redouble my affection towards her who now held such an important place in my heart. Then I handed him my rosary to bless, and left the confessional so free and happy that I can say I had never before in my life experienced such joy.” (Ibid., 35)

Consecration to Mary

Until Thérèse was nine years old, her sister Pauline took the place of her mother. But in 1881 when Pauline entered the Carmel at Lisieux, her younger sister felt the shock so severely that she came down with a nervous malady from which according to human calculations she was never to be cured. She seemed to be almost constantly in delirium. The doctors were perplexed about the nature of the sickness, but were sure that it could not be cured.

During moments when the pain was less severe, she found special delight in weaving garlands of flowers for Our Lady’s altar. “We were then in the beautiful month of May, when all of nature was adorned with the flowers of springtime; only the little flower was languishing and seemed destined to die. That is until she received sunlight from above, and that sunlight was the miraculous statue of the Queen of Heaven.” (Ibid., 50)

Often in the course of her illness, she turned towards the statue of Our Lady and asked to be cured. Her father wrote to Paris to have some Masses celebrated in the Sanctuary of Notre Dame des Victoires, asking for the cure of his “poor little queen.” At the same time a novena was begun to the Blessed Virgin, but no sign of improvement. In fact, Thérèse became steadily worse until she could not even recognize those who stood beside her. Finally, on the Sunday before the novena ended, during a spasm of delirious pain while her sisters were praying before the statue of the Immaculate Heart, “I also turned to our Heavenly Mother,” she relates, “begging her with all my heart to have pity on me. All of a sudden the statue became alive! The Virgin became beautiful, so beautiful that I could never find words to express it…But what penetrated to the roots of my being was her ravishing smile. At that moment all my pains vanished.” (Ibid., 51)

May 8, 1884, at the age of ten, she made her First Communion with the Benedictine nuns at Lisieux, after a fervent retreat of three days. In that first meeting, or, as she expresses it, “fusion” with Jesus, it was her Heavenly Mother again, in the absence of her mother on earth, who accompanied her to the altar. For “it was she herself who on that morning of the 8th of May placed her Jesus into my soul.” (Ibid., 60)

In the afternoon of that happy day, she solemnly ratified Mary’s gift to her by consecrating herself “with all the affection of my heart” to the Blessed Mother of God. “I pronounced the Act of Consecration to the Blessed Virgin in the name of my companions. Doubtless I was chosen for this because I was left without my mother on earth…In consecrating myself to the Virgin Mary, I asked her to watch over me, placing into the act all the devotion of my soul, and it seemed to me, I saw her once again looking down and smiling on her ‘petite fleur.’” (Ibid.)

But this general consecration to Mary did not satisfy the ardent heart of Thérèse. She wished to dedicate herself in a very special way. “I resolved therefore,” she says, “to consecrate myself in a particular way to the Most Holy Virgin, begging for admission among the Daughters of Mary.” And so, on May 31, 1887, she was enrolled in the Association of the Daughters of Mary, at the convent of the Benedictine Abbey of Lisieux, among whom were admitted only those students who were distinguished for their piety and good example. “The same year,” she adds, “in which I was received as a Daughter of the Blessed Virgin, she took away from me my beloved sister Mary, the only solace of my soul … As soon as I heard of her decision to leave, I resolved never again to take any pleasure in things here below.” (Ibid. 68)

Already since the age of three, Thérèse had a strong desire to enter the Carmelites. And now her sister’s entrance intensified this attraction. But there were obstacles in the way. One was her extreme sensitivity, considered irreconcilable with the Carmelite way of life. What to do? She betook herself to her Heavenly Mother who, on Christmas night, 1886, happily freed her from this impediment. However, a more serious obstacle still remained: she was too young to be received.

First Conquests of Mary

The words of Christ on the Cross, “I thirst,” inspired St. Thérèse with “an indescribable zeal for souls.” More specifically, “I wished to give to my Beloved the drink He desired. And I felt myself consumed by a thirst for souls, wishing at any price to save sinners from the eternal flames” of hell. (Ibid. 73) In this apostolate of prayer and sacrifice, she always depended on Mary. Thus at Buissonnets, she heard of a middle-aged servant woman who had lost her faith, and whom no one could bring back to God. Thérèse tried to convert her, but seeing that her efforts were being wasted, she finally took from her own neck a medal of the Blessed Virgin, gave it to the unhappy woman and extracted from her the promise to wear the medal until death. Roschini, quoting Carbonel, La Picola Teresa, c. 22, notes that she was also in the habit of sewing medals of Our Lady into workmen’s clothing – unknown, of course, to the workmen themselves,

However, the outstanding convert of Thérèse’s early apostolate was undoubtedly the notorious Pranzini. A criminal who had stained his hands many times with human blood, he still retained some kind of devotion to the Mother of God. Condemned to death by the courts in Paris, he had refused the ministrations of a priest. While awaiting his execution set for the last day of August he asked for permission to hear Mass on the Feast of the Assumption. At this time he declared publicly that even after entering on his life of crime, he seldom failed to stop in a church to greet La Madonna and that in Alexandria, where he was born, he once had the privilege of carrying a banner of the Blessed Virgin in a religious procession. A devoted client of Mary could not be lost. And as the story of the Little Flower informs us, the Blessed Mother inspired St. Thérèse to offer prayers and sacrifices to God for Pranzini’s conversion. “The news,” writes Thérèse, “became daily more discouraging…to the very last hour Pranzini refused to see a priest.” Still she continued hoping that somehow the impossible would happen, pleading with our Lord that, “He is my first sinner, and for this reason I ask You to give me a sign of his repentance, simply for my consolation…I am sure that You will pardon this unfortunate Pranzini.” (Autobiography, 73.)

And there was a sign, as detailed by the newspapers. “On the morning of August 31, Pranzini had already climbed the guillotine…Then, seized by a sudden inspiration, he swiftly turned around and cried out, ‘M. Curé’, give me your crucifix, quick!’ He added only one more word, ‘I have sinned!’ And the priest cried back, ‘I absolve you.’ A moment later, his head rolled off the guillotine into the dust.” (Roschini, 210)

Pilgrimage to Rome

In 1887, Thérèse was only fourteen years old, too young to enter the Carmelite cloister. So had judged her sister Marie, the Prioress, the Superior of Carmel, and the Archbishop of Bayeux. No one remained but the Pope. And she went to the Pope, in the company of her father. The Blessed Virgin showered this pilgrimage with untold graces. “Arrived in Paris,” she says, “my father wanted me to visit all the places of interest, but of such I found only one, Our Lady of Victories. What I experienced in her Sanctuary is past description; when the graces she brought me were like those I had received at my First Communion…She told me clearly that it was she who had smiled upon me and cured me.” (Autobiography 89-90) While the original purpose of the Roman journey was not to obtain the Pope’s consent, in the course of the pilgrimage Thérèse decided on this resolution, and thus changed an audience of devotion into a successful petition for entrance into Carmel

Finally in Rome, on November 20, 1887, she asked the Holy Father, Leo XIII, for permission to enter Carmel at the age of fifteen. The Pope referred the decision to her immediate superiors. And so, on April 9 the following year, the transferred feast of the Annunciation, Thérèse Martin realized her life’s ambition of entering the Order of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel.

In the Order of Carmel

January 10, the generous postulant took the habit of the Virgin of Carmel. But then she was told to wait a few months after the novitiate before making her first profession. This was a hard sacrifice, but “the Blessed Virgin,” she confessed, “helped me to prepare the vesture of my soul.” Moreover, there was the reward of having her profession take place on Mary’s Birthday. “The Nativity of Mary,” she exclaimed, “what a perfect feast on which to become the spouse of Jesus!” On the 24th of the same month, the Feast of Our Lady of Mercy, the ceremony of taking the veil took place. Not long after, obedience called her to assume the delicate office of mistress of novices. But her guide in everything was always the Seat of Wisdom. Thus she confided to her spiritual charges who marveled at her knowledge of their souls, “I never make any observation without first invoking the Blessed Virgin. I ask her to inspire me to say what is most for your good; and often I am surprised myself at what I am telling you.” (Roschini, 215)

Life of Union with Mary

Her life of union with the Mother of God became daily more intense. According to the late Prioress of Carmel at Lisieux, what contributed not a little to this was the classic treatise, “On the True Devotion of Blessed Virgin Mary,” by St. Louis de Montfort, which Thérèse frequently read and meditated upon. Following Louis de Montfort’s advice, she did everything with Mary, or rather, in the presence of Mary, under Mary’s influence and according to her example.

The very name of Mary was enough “to transport her heart with joy.” Her prayer to Our Lord was that He would always remember her as the daughter of the same Mother as Himself. This thought so fascinated her that she never tired of repeating it. “Everything is mine,” she wrote Oct. 19, 1892, to her sister Céline, “God is mine, and the Mother of God is also my Mother, … something I find myself saying to her, ‘You know, dear Mother, that I am happier than you? I have you for Mother, whereas you do not have the Blessed Virgin to love…I poor creature am not your servant, but your daughter. You are the Mother of Jesus, and my Mother too.’” And in an outburst of love she was prompted to say, “O Mary, if I were Queen of heaven and you were Thérèse, I would wish to be Thérèse, to see you Queen of Heaven.” These were the last words written by the saint, three weeks before her death, on a picture of Our Lady of Victories.

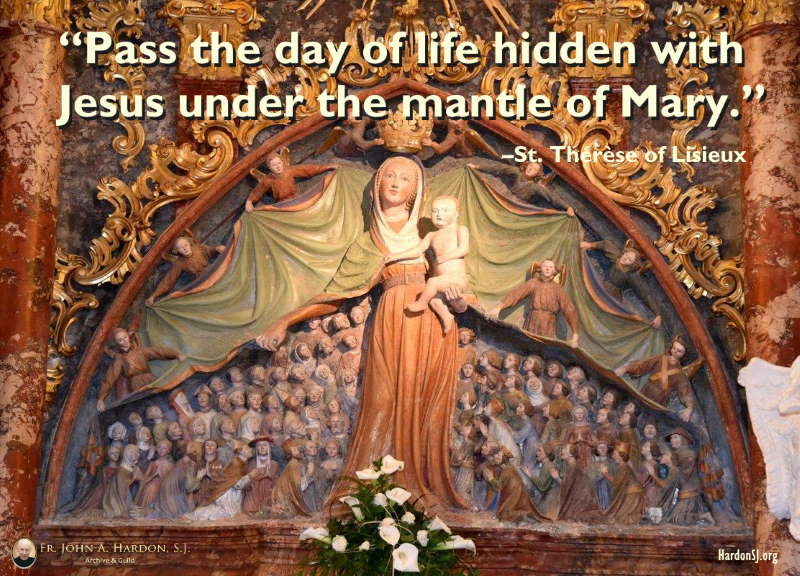

Her ardent wish was “to live during this sad exile in the company of Mary, submerged in loving ecstasy in the depths of her maternal Heart,” that she should “pass the day of life hidden with Jesus under the mantle of Mary,” declaring that there alone she “finds the prelude of Paradise.” When in trial or difficulty she had recourse to Mary, “whose glance alone is enough to dissipate every fear.” (Quoted from Histoire d’ une Ame, pp. 379, 423, 428)

She lived especially in the presence of her Blessed Mother when fulfilling the most important act of the day: receiving Holy Communion. This was her method: “I picture to myself my soul as an open field from which I ask the Blessed Virgin to remove the obstacles which are my imperfections.” And again, “At the moment of Communion, I sometimes imagine my soul is a child of three or four years, who has just come from play, hair disheveled, and clothes disorderly and soiled. These are the injuries that I meet in combating with souls…. Then comes the Blessed Virgin and in a moment makes me respectable looking and fit to assist at the Banquet of the Angels without shame.” (Autobiography, 254)

However, Thérèse had resolved not only to live and work under Mary’s watchful eyes, but also to follow her example. She wished “to follow every day” in the footsteps of her Mother, especially in learning from her “how to remain little.” Mary taught her that “suffering out of love is a joy.” But more than anything else, she instructed her in simplicity, in the practice of that characteristic virtue of “the little way.” Thus in a poem she wrote for one of her young postulants, she has the Blessed Virgin telling her that, “the one virtue above all others that I am giving you is simplicity.” (Histoire, 425)

Apostolate through Mary

There are 238 letters of St. Thérèse in the latest collection, edited by l’Abbé Combes in 1947. In the spirit of the canonical rule of not concluding a Process of Beatification till fifty years after the death of a Servant of God, the Carmelite Superiors of Lisieux waited until now to publish all the extant correspondence of the Little Flower. This correspondence gives us an insight into what may be called the external apostolate of the Patroness of the Missions. Running through the letters is a spirit of reliance on the example and assistance of the Mother of God that is truly remarkable.

On October 14th, 1890, shortly after Thérèse took the veil, she wrote to her sister Céline who was making a pilgrimage to Paray-le-Monial. After exhorting her to a great purity of heart, she continues: “Virginity is a profound silence of all this world’s cares, not only useless cares, but all cares….To be a virgin one must have no thought left save for the Spouse, who will have nothing near Him that is not virginal, since He chose to be born of a Virgin Mother….Again it has been said that every one has a natural love for the place of his birth, and as the place of Jesus’ birth is the Virgin of virgins and Jesus was born, by His choice, of a Lily, He loves to be in virgin hearts.”

A year later (July 8, 1891) she is writing to Céline about a certain Hyacinthe Loyson, who apostatized from the priesthood. Again the burden of her letter is a plea for holiness, but now as a sacrifice to obtain Loyson’s conversion through the Mother of God. “We must not grow weary of praying” for the unfortunate man, she says. “Confidence works miracles…. And in any event it is not our merits but those of our Spouse, which are ours, that we offer to our Father who is in heaven, in order that our brother, a son of the Blessed Virgin, should come back vanquished to throw himself beneath the cloak of the most merciful of mothers.” Thérèse, who had prayed for the apostate throughout her religious life, offered her last Communion for him in 1897, August 19, the feast of St. Hyacinthe. Loyson is known to have been converted on his death bed, fifteen years later.

On the Feast of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, in 1894, Thérèse wrote to her cousin, Mme. Pottier, to congratulate her on her husband’s return to the practice of his faith. Mme. Pottier had gone to Lourdes to ask for the grace of his conversion. “Your letter,” she writes, “gave me great joy; I am lost in wonder at the way the Blessed Virgin has pleased to grant all your desires. Even before your marriage, she wanted the soul, to which you were to be united, to be but one soul with yours through identity of feeling. What a grace to feel yourself so completely understood! and above all to know that your union will be immortal, that after this life you will still be able to love the husband who is so dear to you… I had asked Our Lady of Mt. Carmel for the grace you obtained at Lourdes.” And she adds, “I am so happy that you are wearing the Blessed Scapular it is a sure sign of predestination.”

For several years before her death, Soeur Thérèse kept in correspondence with various priests and clerics engaged in missionary work, or preparing for the same. The day after Christmas, 1896, she sent a letter of encouragement to a young priest who was soon to leave his family for the foreign mission field. “Jesus knows,” she tells him, “that the suffering of people dear to you makes your own greater still; but He too suffered that martyrdom to save our souls. He left His Mother, He saw the Immaculate Virgin at the foot of the Cross, her Heart pierced by a sword of sorrow; so I hope that our Divine Lord will comfort your dear mother, and my prayer for that is most urgent.”

One of the longest and probably most light-hearted letters of St. Thérèse was penned (dated March 19) in 1897 the year of her death. Père Roulland, a missionary in China, had asked her to suggest a name for baptism. “You ask me,” she answered, “to choose between the two names, Marie or Thérèse, for one of the girls you are to baptize. Since the Chinese don’t want two saints to protect them but only one, they must have the more powerful, so the Blessed Virgin wins.”

Writing to the same missionary two months later, she confided to him her conviction that all missionaries are not only saved but will not even pass through Purgatory to enter heaven “How can God,” she asks, “purify in the flames of Purgatory souls consumed in the fires of divine love? Of course no human life is free from faults, only the Immaculate Virgin presents herself in absolute purity before God’s majesty. What a joy to remember that she is our Mother! Since she loves us and knows our weaknesses, what have we to fear? What a lot of phrases to express my thought….I simply wanted to say that it seems to me that all missionaries are martyrs by desire and will, and that, in consequence, not one should go to Purgatory. If, at the moment they appear before God, some traces of human weakness remain in their souls, the Blessed Virgin obtains for them the grace to make an act of perfect love, and then gives them the palm and the crown they have so truly merited.”

Last Days and Death

On the day of her profession, Thérèse had asked Our Lord, as a nuptial gift, “the martyrdom of heart and body.” She obtained both. During Holy Week in 1896, she had the first flow of blood from her lungs; but she was not taken to the infirmary until July of the following year. She herself remarked that on entering the infirmary, her first glance rested on the miraculous statue of the Blessed Virgin, which was brought there to keep her company. Witnesses say that she was favored on this occasion with another visitation from the Blessed Mother, judging by the transport of joy that covered her face and the subsequent testimony which she gave.

She had hoped to die on the sixth of August, the Feast of the Transfiguration, but in vain. It was during these final weeks before her death that she gave expression to some of the noblest sentiments about the Mother of God to be found in the lives of the saints. One day she was heard to exclaim: “How I love the Blessed Virgin! If I had been a priest, how I should have spoken of her. She is sometimes described as unapproachable, whereas she should be represented as easy of imitation. She is more Mother than Queen. I have heard it said that her splendor eclipses that of all the saints as the rising sun makes all the stars disappear. It sounds so strange. That a Mother should take away the glory of her children! I think quite the reverse. I believe that she will greatly increase the splendor of the elect….Our Mother Mary….How simple her life must have been.” (Autobiography, 208)

She begged the Blessed Virgin to remind her Divine Son of the title of “thief” which He gave Himself in the Gospels, that He might not forget to come and steal her soul. But two months of martyrdom still separated her from that liberation. Eagerly looking forward to death, she complained, “It might be said that the angels were given orders to hide from me the light of my approaching end.” When asked if her Mother Mary also concealed this knowledge from her, she answered, “She would never hide that from me because I love her too much.” (Roschini, 223)

Finally on the morning of September 30, she observed that this had been her last night on earth, and added, “How fervently I have prayed to Our Lady….And yet it has been pure agony, without a ray of consolation.” Towards three o’clock in the afternoon, seized with a convulsion that shook her whole body, she opened her arms in the form of a cross. The Superior placed an image of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel on her knees. Thérèse looked at it for a moment and said, “Mother, recommend me quickly to the Blessed Virgin. Prepare me for a happy death.” Three hours later, as the monastery bell was ringing out the Angelus, with her eyes fixed on Our Lady’s statue, she passed into eternity.

Review for Religious

Vol. 11, March 1952, pp. 75-84

Copyright © 1998 by Inter Mirifica