Cardinal Newman, Apologist of Our Lady

by Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J.

In their formal protest in 1950 against the definition of Our Lady’s Assumption, the Anglican bishops of England declared, “We profoundly regret that the Roman Catholic Church has chosen by this act to increase dogmatic differences in Christendom and has thereby gravely injured the growth of understanding between Christians based on a common possession of the fundamental truths of the Gospel” (London Times, August 18, 1950).

In their formal protest in 1950 against the definition of Our Lady’s Assumption, the Anglican bishops of England declared, “We profoundly regret that the Roman Catholic Church has chosen by this act to increase dogmatic differences in Christendom and has thereby gravely injured the growth of understanding between Christians based on a common possession of the fundamental truths of the Gospel” (London Times, August 18, 1950).

We may assume that the Bishops of York and Canterbury were sincere in making this declaration, but how should we estimate and deal with their attitude of mind, which is so common among Christians outside the true Church? Why should faith in Mary, as one Protestant theologian puts it, be the “sword of separation” between Catholic and non-Catholic Christianity? Fortunately, we have an excellent guide in this matter in Cardinal Newman, who himself passed through all the stages of prejudice against Catholic devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and finally became an outstanding defender of her dignity against the attacks of her enemies.

Newman’s Anglican Devotion to Mary

Newman became a Catholic in 1845, after forty-four years in the established Church of England. Long before his conversion, however, he was already devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Among the early influences in his life at Oxford was Hurrell Froude who “taught me to look with admiration towards the Church of Rome. He fixed deep in me the idea of devotion to the Blessed Virgin.” Froude had “a high severe idea of the intrinsic excellence of Virginity; and he considered the Blessed Virgin its great Pattern.” (A., 22, 23) [1]

Throughout his Anglican days, Newman often preached on the dignity of Christ’s Mother, stressing especially her transcendent purity and nearness to God. He never tired of repeating that Christ was born of a Virgin “pure and spotless.” To his mind, it was inconceivable that the only-begotten Son of God should have come into the world as other men. “The thought may not be suffered that He should have been the son of shame and guilt; He came by a new and living way; He selected and purified a tabernacle for Himself, becoming the immaculate seed of the woman, forming His body miraculously from the substance of the Virgin Mary” (P., 31)

On the Feast of the Annunciation in 1832, he preached a sermon on Mary’s sanctity in which he was accused of teaching the Immaculate Conception. “That which is born of the flesh,” he said, “is flesh.” So that no one can bring what is clean from what is unclean. In view of her prospective dignity as the Mother of Christ, Mary was endowed with gifts of holiness that are beyond description. “What must have been the transcendent purity of her whom the Creator Spirit condescended to overshadow with His miraculous presence…This contemplation runs to a higher subject, did we dare follow it; for what, think you, was the sanctified human state of that human nature of which God formed His sinless Son?” (P., 132.) Newman would not draw the illation, but his audience did.

Later in life he referred to his sermon as a witness to his abiding affection for the Blessed Virgin Mary. “I had a true devotion to the Blessed Virgin,” he says, speaking of his Oxford days, “in whose college I lived, whose Altar I served, and whose Immaculate Purity I had in one of my earliest printed sermons made much of” (A., 149).

Early Prejudices Against “Mariolatry”

Against this inspiring background, we are surprised to find certain blindspots and inconsistencies in Newman’s Anglican devotion to the Virgin Mother. Until a few years before his conversion, he hesitated to call Mary the Mother of God. Convinced, it seems, of the fact of her divine maternity, he could not bring himself to give her this exalted title. The Son of God, he preached, “came into this world, not in the clouds but born of a woman; He the Son of Mary, and she (if it may be said) the Mother of God” (P., 32).

Some of Newman’s critics have remarked on the length of time he spent in coming to a decision about entering the Roman Church. The fifteen years before his conversion he spoke of “the high gifts and strong claims of the Church of Rome on our admiration, reverence, love and gratitude.” He would ask himself how a non-Catholic can withstand her attractiveness, how he can “refrain from being melted into tenderness and rushing into communion” with her, on beholding the Church’s beauty of doctrine and vindication of her Apostolic name.

Newman answers for himself. On the one hand he found the Roman Church most attractive in her doctrine and ritual; on the other hand, he resisted her advances. “My feeling,” he confessed, “was something like that of a man who is obliged in a court of justice to bear witness against a friend” (A., 50). There was a conflict between “reason and affection,” between what he thought his reason told him against the errors of Rome, and what his spontaneous Christian affections loved in Roman Catholicism.

Now the strange fact is that Newman reduced all his Anglican objections to the Church of Rome to one basic element in her system, namely, her devotion to the saints and particularly to the Mother of God. Writing as a Catholic, he says “I thought the essence of her (the Roman Church’s) offence to consist in the honours which she paid to the Blessed Virgin and the saints, and the more I grew in devotion, both to the saints and to our Lady, the more impatient I was at the Roman practices, as if those glorified creations of God must be severely shocked, if pain could be theirs, at the undue veneration of which they were the objects” (A., 48).

One day, as an Anglican, he summarized the pros and cons for becoming a Catholic. Point six in a series of nine is clear: “I could not go to Rome, while she suffered honours to be paid to the Blessed Virgin and the Saints which I thought in my conscience to be incompatible with the Supreme, Incommunicable Glory of the One Infinite and Eternal” which belong solely to God (A., 134).

Four years before his conversion, in 1841, he received an appeal from a zealous Catholic layman urging him not to hesitate any longer about submitting to Rome, when so little doctrinal difference separated the Anglicans from the true Church. Newman replied in a long letter, in which he said, “I fear I am going to pain you by telling you, that you consider the approaches in doctrine on our part towards you closer than they really are. I cannot help repeating what I have many times said in print, that your services and devotions to St. Mary in matter of fact do most deeply pain me. I am only stating it as a fact” (A., 173).

A year later, Newman wrote to Dr. Russell to thank him for an English translation of St. Alphonsus Liguori’s sermons. Dr. Russell, who was president of Maynooth in Dublin, had, says Newman, “perhaps more to do with my conversion than anyone else.” In the letter, Newman asked his friend whether anything had been left out in the translation of Liguori’s sermons, and was told that there had been omission in one sermon about the Blessed Virgin. This small detail appears to have been the turning point in Newman’s approach to the Church. Describing it in the Apologia he says, “It must be observed that the writings of St. Alfonso, as I knew them by the extracts commonly made from them, prejudiced me as much against the Roman Church as anything else, on account of what was called their ‘Mariolatry.’” But, and this is significant, “there is nothing of the kind in this book” which Russell had sent him. “This omission in the case of a book intended for Catholics, at least showed that such passages as are found in the works of Italian authors were not acceptable to every part of the Catholic world. Such devotional manifestations in honour of our Lady had been my great crux as regards Catholicism” (A., 176).

Once he became convinced that the Roman Church was willing to distinguish between faith and external piety in devotion to Mary, and to recognize that piety, unlike faith, can be different for different people, his entrance into the Church was only a matter of time. The letter to Dr. Russell was sent in November 1842, and in February of the following year, Newman made a formal public retraction “of all the hard things which I had said against the Church of Rome” (A., 181).

In Defense of Mary’s Honor

After his conversion, Newman drew frequently on his own experience to help remove the obstacles which others had to face in their journey to Rome—notably the common prejudice against so-called Catholic excesses in devotion to the Blessed Virgin. However, for the most part hits was only private and personal assistance to prospective converts or in answer to specific charges made by individual Protestants. Not until 1865 did he have an opportunity to defend Mary’s honor and to vindicate the Roman piety in her regard in a way that was to win for him the gratitude of generations of English-speaking Catholics.

In 1865 his old friend Edward Pusey published the Eirenicon, in which he promised a peaceful settlement of the differences between Canterbury and Rome, if only Rome would meet certain conditions which he recommended. One of the major obstacles which had to be removed in the interest of re-union was the Roman Church’s cultus of the Mother of God. “I believe,” he said, “the system in regard to the Blessed Virgin is the chief hindrance to re-union.” Of all the objections which the average Englishman has against Rome, “the vast system as to the Blessed Virgin … to all of us has been the special crux of the Roman system” (Eirenicon, 101)

Pusey opposed the current Catholic devotion to the Blessed Virgin on two scores: he claimed it was simply excessive, and it lacked a solid foundation in Christian tradition. He singled out for special censure the dogma of the Immaculate Conception which had just been defined eleven years before. This was the quintessence of papal presumption in defining as revealed doctrine what only a handful of zealots had originally believed to be true.

Pusey’s main difficulty, however, was similar to what Newman’s had been, that Catholic piety towards Mary was derogating from the honor that was rightly due to her Son. Statements like “God does not will to give anything except through the Blessed Virgin,” and “He has placed her between Christ and the Church” were unintelligible, he thought, if Christ is the sole Mediator between God and man. Granted that “the devotion of the people to the Blessed Virgin outruns the judgment of the priests,” but what “if the whole weight of Papal authority is added to the popular doctrines, and the people are bidden … to be still more devoted to the Blessed Virgin … one sees not where there shall be any pause or bound short of that bold conception that ‘every prayer, both of individuals and of the Church, should be addressed to St. Mary’” (Eirenicon, 186, 187).

Newman’s answer to Pusey, while called a Letter, extends to 170 pages in Longmans’ edition. The body of the letter falls into three parts, each dealing with a separate charge made by Pusey. It has been justly called a “masterpiece of Marian literature,” which deserves to be better known not only as a revelation of Newman’s own love for Our Lady, but as a source book of apologetics to defend our Catholic devotion to the Mother of God.

Marian Doctrine Not Marian Devotion

“I begin,” says Newman, “by making a distinction—the distinction between faith and devotion.” By faith in the Blessed Virgin he means all that Catholics believe has been revealed to us about the Mother of God. By devotion he means such religious honors and expressions of affection as follow from the faith. “Faith and devotion are as distinct in fact as they are in idea. We cannot, indeed, be devout without faith, but we may believe without feeling devotion.” Against the Protestant objection that Catholic doctrine about Mary has grown by accretion over the centuries, Newman answers that what has grown in subjective devotion, that is, realization and expression of faith, but not the faith itself. And again, in certain countries Catholics are accused of making almost a goddess of the Madonna, while elsewhere their piety is more restrained. The same distinction applies; without defending genuine excesses, it is still true that some Catholics are more affectionate and expressive in their devotions than others, but the doctrine about Mary is always the same.

“This distinction,” for Newman, “is forcibly brought home to a convert, as a peculiarity of the Catholic religion, on his first introduction to its worship. The faith is everywhere the same, but a large liberty is accorded to private judgment and inclination as regards matters of devotion … No one interferes with his neighbor; agreeing, as it were, to differ, they pursue independently a common end, and by paths, distinct but converging, present themselves before God” (L. P., 28).

Starting from this distinction, Newman proceeds to explain some of the fundamental doctrines which Catholics hold regarding the Blessed Virgin. Her Immaculate Conception, for example, is a stumbling block to non-Catholics because they do not know what we mean by original sin. “Our doctrine of original sin is not the same as the Protestant. We with the Fathers think of it as something negative, Protestants as something positive.” They hold that “it is a disease, a radical change of nature, an active poison internally corrupting the soul, infecting its primary elements, and disorganizing it; and they fancy we ascribe a different nature from ours to the Blessed Virgin, different from that of her parents, and from that of fallen Adam.” We hold nothing of the kind. “We consider that in Adam she died as others; that she was included, together with the whole race, in Adam’s sentence … but we deny that she had original sin; for by original sin we mean something negative, the deprivation of that supernatural unmerited grace which Adam and Eve had on their first formation.”

Catholic belief in the Immaculate Conception is only a natural corollary to the more fundamental truth of the Divine Maternity. Newman is a specialist here, tracing the clear lines of tradition from the earliest Fathers of the Church. To the Greeks she was Theotokos, to the Latins Deipara, to us the Mother of God. Into one paragraph he crowds the testimony of the ages on the elemental dignity of the Virgin Mary. “Our God was carried in the womb of Mary,” says Ignatius who was martyred A.D. 106. “The Maker of all,” says Amphylochius, “is born of a Virgin.” “God dwelt in a womb,” says Proclus. Cassian says, “Mary bore her Author.” “The Everlasting,” says Ambrose, “came into the Virgin.” “He is made in thee,” says St. Augustine, “Who made thee.” (L.P., 47, 65).

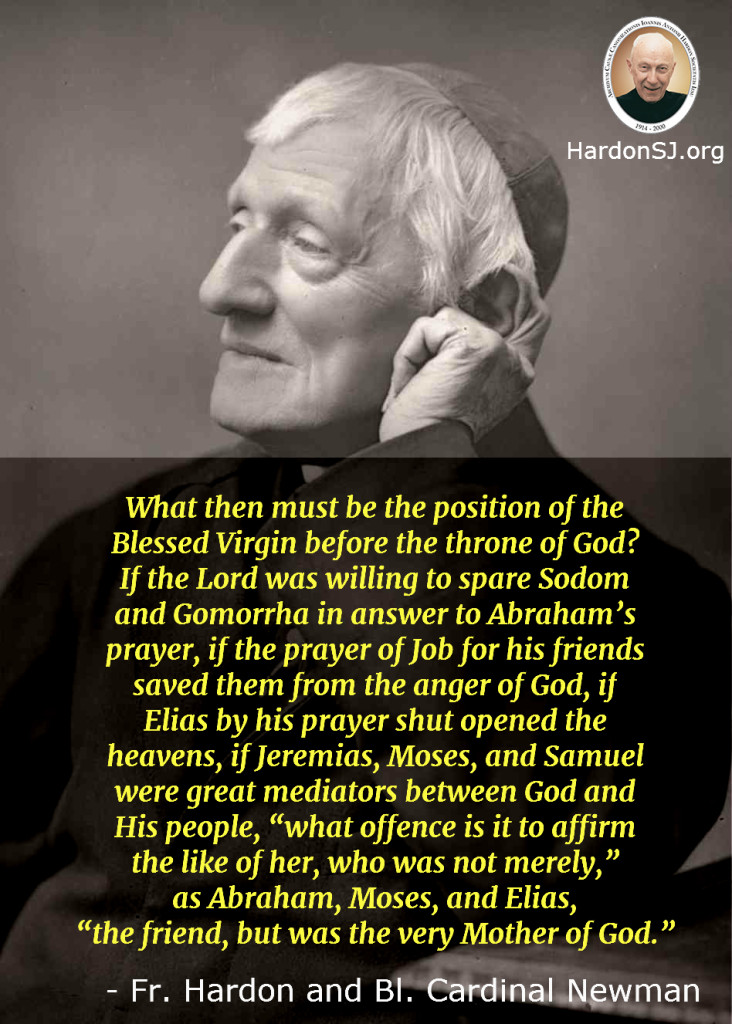

On the practical side, Newman deals with the question of Mary’s intercessory power which, he explains, follows from two basic truths: first that it is good and useful to invoke the saints, and secondly that the Blessed Virgin is singularly dear to her Son. The first may be assumed among believing Christians, but the second is not so obvious. Granting that prayer of intercession is “a first principle of the Church’s life, it is certain again that the vital force of that intercession, as an availing power, is sanctity. The words of the man born blind speak the common-sense of nature: ‘If any man be a worshipper of God, him He heareth.’” What then must be the position of the Blessed Virgin before the throne of God? If the Lord was willing to spare Sodom and Gomorrha in answer to Abraham’s prayer, if the prayer of Job for his friends saved them from the anger of God, if Elias by his prayer shut opened the heavens, if Jeremias, Moses, and Samuel were great mediators between God and His people, “what offence is it to affirm the like of her, who was not merely,” as Abraham, Moses, and Elias, “the friend, but was the very Mother of God” (L.P., 71, 72).

Doctrine About Mary Affected by Devotion

Having laid the doctrinal foundation for Marian piety, Newman examines the charges made by Pusey that Catholic devotion to the Blessed Virgin is excessive and out of proportion to its dogmatic basis. This accusation would be justified only if man were all intellect and his religion were only intellectual. But “religion acts on the affections.” And “who is to hinder these, when once roused, from gathering in their strength and running wild? Of all passions, love is the most unmanageable; nay more, I would not give much for that love which is never extravagant, which always observes the proprieties, and can moved about in perfect good taste, under all circumstances. What mother, what husband or wife, what youth or maiden in love, but says a thousand foolish things, in the way of endearment, which the speaker would be sorry for strangers to hear, yet they are not on that account unwelcome to the parties to whom they are addressed” (L.P., 79, 80).

Let me apply what I have been saying to the teaching of the Church on the subject of the Blessed Virgin…When once we have mastered the idea that Mary bore, suckled, and handled the Eternal in the form of a child, what limit is conceivable to the rush and flood of thoughts which such a doctrine involves? What awe and surprise must attend upon the knowledge that a creature has been brought so close to the Divine Essence? It was the creation of a new idea and of a new sympathy, of a new faith and worship, when the holy Apostles announced that God had become incarnate; then a supreme love and devotion to Him became possible, which seemed hopeless before that revelation. This was the first consequence of their teaching. But besides this, a second range of thoughts was opened on mankind, unknown before, and unlike any other, as soon as it was understood that that Incarnate God had a mother” (L.P., 83).

Mariolatry is a familiar reproach on the lips of Protestants and of Newman himself before his conversion. But it is based on a libel. The two ideas of Christ as Mediator and of Mary as mediatrix are perfectly distinct in the minds of Catholics, and there is no interference between them. “He is God made low, she is woman made high … When he became man, He brought home to us His incommunicable attributes with a distinctness which precludes the possibility of lowering Him merely by our exalting a creature. He alone has an entrance into our soul, reads our secret thoughts, speaks to our heart, applies to us spiritual pardon and strength … Mary is only our Mother by divine appointment, given us from the Cross; her presence is above, not on earth; her office is external, not within us. Her power is indirect. It is her prayers that avail, and her prayers are effectual by the fiat of Him Who is our all in all.”

It is true that Mary occupies a center in Catholic devotion and worship, but that center is infinitely removed from divinity. “If we placed our Lady in that centre, we should only be dragging Him from His throne, and making Him an Arian kind of God, that is, no God at all.” Then follows a terrible indictment against his own contemporaries and those modern Protestants who accuse Catholics of adoring the Virgin Mother. “He who charges us,” says Newman, “with making Mary a divinity is thereby denying the divinity of Jesus. Such a man does not know what divinity is” (L.P., 83-85).

Catholic Excesses

In the final part of his letter, Newman handles the accusation that devotion to Mary obscures the devotion to Christ. Protestants say that “our devotions to our Lady must necessarily throw our Lord into the shade; and thereby relieve themselves of a great deal of trouble. Then they catch at any stray fact which countenances or seems to countenance their prejudices. Now I say plainly, I will never defend or screen any one from your just rebuke who, through false devotion to Mary, forgets Jesus. But I should like the fact to be proved first, I cannot hastily admit it. There is this broad find, on the whole, that just nations and countries have lost their faith in the divinity of Christ, who have given up devotion to His Mother, and that those on the other hand, who had been foremost in her honour, have retained their orthodoxy. Contrast, for instance, the Calvinists with the Greeks, or France with the North of Germany, or the Protestants and Catholic communions in Ireland . . . . In the Catholic Church Mary has shown herself, not the rival, but the minister of her Son; she has protected Him, as in His infancy, so in the whole history of the Religion” (L.P., 92, 93).

Non-Catholics make much of the fact that Catholic churches are filed with statues and pictures of the Blessed Virgin, that there are so many prayers in her honor, that she is given so important a place in the liturgy. Newman answers with two distinctions: first it is not true that Mary enjoys the center of devotion in the liturgy, and secondly, Protestants judge Catholics by themselves when they assume that what should be idolatrous or dishonorable to Christ among themselves is also the same among Catholics. Thus “when strangers are so unfavorably impressed with us, because they see Images of our Lady in our Churches, and crowds flocking about her, they forget that there is a Presence within the sacred walls, infinitely more awful, which claims and obtains from us a worship transcendently different from any devotion we pay to her. That devotion might, indeed, tend to idolatry, if it were encouraged in Protestant churches, where there is nothing higher than it to attract the worshipper; but all the images that a Catholic church ever contained, all the Crucifixes at its Altars brought together, do not so affect its frequenters, as the lamp which betokens the presence or absence there of the Blessed Sacrament.”

“The Mass again conveys to us the same lesson of the sovereignty of the Incarnate Son; it is a return to Calvary, and Mary is scarcely named in it.”

In the same way, Holy Communion, “which is given in the morning, is a solemn unequivocal act of faith in the Incarnate God, if any be such; and the most gracious admonitions, did we need one, of His sovereign and sole right to possess us. I knew a lady, who on her deathbed was visited by an excellent Protestant friend. The latter, with great tenderness for her soul’s welfare, asked her whether her prayers to the Blessed Virgin did not at that awful hour, lead to forgetfulness of her Savior. ‘Forget Him?’ she replied. ‘Why He was just now here.’ She had been receiving Him in communion” (L. P., 95, 96).

Newman had one last and the most difficult rebuttal to make. Pusey had drawn up a list of quotations from various Catholic writers who speak of the Blessed Virgin in terms of extravagant affection. But this is an unfair criticism. “Some of your authors,” Newman admits, “are Saints; all, I suppose, are spiritual writers and holy men; but the majority are of no great celebrity, even if they have any kind of weight. Suarez has no business among them at all, for, when he says that no one is saved without the Blessed Virgin, he is speaking not of devotion to her, but of her intercession. The greatest name is St. Alfonso Liguori; but it never surprises me to read anything extraordinary in the devotions of a saint.”

However, when faced directly with Pusey’s quotations, Newman confesses, “I will frankly say that when I read them in your volume, they affected me with grief and almost with anger; for they seemed to ascribe to the Blessed Virgin a power of searching the reins and hearts, which is the attribute of God alone; and I said to myself, how can we any longer prove our Lord’s divinity from Scripture, if those cardinal passages which invest Him with divine prerogatives, after all invest Him with nothing beyond what His Mother shares with Him? And how again, is there anything of incommunicable greatness in His death and passion, if He who was alone in the garden, alone upon the cross, alone in the resurrection, after all is not alone, but shared His solitary work with His Blessed Mother. And then again, if I hate those perverse sayings so much, how much more must she, in proportion to her love of Him? and how do we show our love for her, by wounding her in the very apple of her eye? This I felt and feel; but then on the other hand I have to observe that these strange words after all are but few in number; that most of them exemplify the difficulty of determining the exact point where truth passes into error, and that they are allowable in one sense or connection, though false in another. Thus to say that prayer (and the Blessed Virgin’s prayer) is omnipotent, is a harsh expression in every-day prose; but, if it is explained to mean that there is nothing which prayer may not obtain from God, it is nothing else than the very promise made us in Scripture” (L.P., 103, 104).

Pusey’s worst accusation was that according to certain Catholic writers devotion to the Blessed Virgin is necessary for salvation. Newman challenges this statement, “by whom is it said that to pray to our Lady and the Saints is necessary to salvation? The proposition of St. Alfonso is, that ‘God gives no grace except through Mary, that is through her intercession. But intercession is one thing, devotion another.” If devotion to the Blessed Virgin were necessary, then “no Protestant could be saved; if it were so, there would be grave reason for doubting of the salvation of St. Chrysostom or St. Athanasius, or of the primitive Martyrs; nay, I should like to know whether St. Augustine, in all his voluminous writings, invokes her once. Our Lord died for those heathen who did not know Him; and His Mother intercedes according to His will, and, when He wills to save a particular souls, she at once prays for it. I say, He wills indeed according to her prayer, but then she prays according to His will” (L.P., 105, 106).

Newman’s Apologetic Method

— Its scholarship and transparent honesty made it welcome to those outside the Church, even to Pusey, as he admitted in a letter to Newman. But more important, it gave to Catholics a profound analysis of the principles on which their devotion to the Mother of God should be based. It also gave them an object lesson in the method they should follow in dealing with non-Catholic Christians, with a view to converting them to the true faith. The method must be a consummate respect for the non-Catholic’s sincerity, and should recognize that after all is said and done, faith is a free gift of God to be obtained in answer to humble prayer.

Thus in the beginning of his letter, Newman makes it clear that he considers the opposition to be in good faith. “I know,” he says, “the joy it would give those conscientious men [Pusey and his followers] to be one with ourselves. I know how their hearts spring up with a spontaneous transport at the very thought of union; and what yearning is theirs after that great privilege, which they have not, communion with the see of Peter, and its present, past and future” (L. P., 3).

But after all the claims of conscience are settled by reason and argumentation, the most important thing is still needed. And so in the last paragraph of his letter Newman concludes with a prayer. He asks God to “bring us all together in unity … to destroy all bitterness on your side and ours … to quench all jealous, sour, proud, fierce antagonism on our side; and to dissipate all captious, carping, fastidious refinements of reasoning on yours.” And finally, “May that bright and gentle Lady, the Blessed Virgin Mary, overcome you with her sweetness, and revenge herself on her foes by interceding effectually for their conversion” (L. P. 118).

[1] The key to the references is: A, Apologia (1947): P, Parochial and Plain Sermons, II (1918); L.P., “Letter to Pusey” in Difficulties of Anglicans (1907).